Has someone ever cheerfully informed you that they ‘did that thing for you’ as a favour; no need to thank them…it was their pleasure? You smile somewhat cautiously as they skip out of view, seemingly happy with a good deed done – you open the task ‘completed’ and realise that the next four hours of your life will be undoing and then redoing something that should have only taken half the time. I’ve recently experienced something similar – I was somewhat miffed. Upon reflection on the incident with a line manager I was placated with the line ‘they meant well, it came from a good place’. At the time, this epithet felt shallow and an excuse to forgive what I perceived to be a lack of commitment to a positive outcome. However, when we apply a philosophical cast of mind we open up the ancient debate from the family of ‘means justifying ends’’; to what extent should we forgive a bad outcome if the intention was good?

Good intentions with bad outcomes can be global. Think about the ‘war on drugs’; a policy designed to ameliorate the scourge of drug trafficking and addiction which has led, arguably, to an increase in homicides and no meaningful reduction in drug use and its illicit manufacture. Some argue as well that ‘Food Aid’ falls under this same category.

As with most things that trouble my mind, I am not the first to an encounter this conundrum. The Medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas is credited with introducing what is referred to as the ‘Doctrine of Double Effect’. In his Summa Theologica he argues that killing one’s assailant is justified provided it was not the intention:

“Nothing hinders one act from having two effects, only one of which is intended, while the other is beside the intention” (II-II, Qu. 64, Art.y)”

Self-defence is the perfect example here. If you were being attacked – your act or intention of defending yourself (first effect) is the overriding intended ‘good’ whilst the possibility that your attacker is killed in the exchange is a second effect (hence ‘double effect’) which whilst in itself is bad – you may not be wholly morally responsible as it was ‘beside the intention’.

Now, that all seems pretty reasonable and would appear to be the blueprint for the charge of ‘manslaughter’ within our criminal courts. More often than not acts that ultimately cause death to another person are either premeditated (murder) or accidental/unintended. Before I continue, I should point at that ‘Intention’ in terms of its nature and purpose is hotly debated within the ‘Philosophy of Mind’ and it is not my intention (ah-ha) to dive too deep into that slippery catacomb! This blog post will focus instead on establishing if a more practical ‘micro’ rubric could be established to determine if the means justified the ends or more pertinently – all is forgiven so long as they meant well.

We should quickly establish some parameters. Firstly, we shouldn’t hold children to account for unintended consequences – they are still humans at the beginning of learning and incidences such as helping to clean the cat by putting it in water or adding washing up liquid to the dishwasher to ‘help with the dishes’ are chances to grow and develop (and a chance to really establish higher parenting thresholds).

I would also add those persons experiencing significant mental health issues or chronic difficulty with reasoning should also be given empathy and consideration. To be truly accountable for our actions as persons our capacity to reason must be without doubt. Finally, I should reaffirm that the abstract concept of ‘intention’ can be as atomised or simple depending on how closely you wish to view it. My intention (again, ah-ha) is to examine the maxim that a well-meaning intention forgives a bad outcome within the practical, everyday exchanges between humans.

Let’s set this up with an argument using four numbered premises. If you’ve never seen this sort of thing before, the idea is that I offer four numbered premises (or propositions or statements) with each one leading to the next one with the final premise being the conclusion which should be deductively true. I do it this way to make the argument valid. Whether it’s sound or not is a whole other thing! I then try and justify each premise or at the very least offer arguments for its inclusion to support the conclusion (in this case: Premise 4). This is a standard approach in analytical philosophy and is a good exercise in problem solving! I may end up tweaking the argument and that’s perfectly allowed. Okay, here we go:

(1) Person A intends a good outcome for Person B.

(2) Person A performs action X

(3) Action X results in a bad outcome for Person B.

(4) Person B forgives Person A because of Premise (1).

Now I go through each premise to check their validity and inference.

To get from (1) to (4) we would need for there to be proof that the intention was indeed ‘good’. What is fascinating about this is how we would go about doing this. There’s some Kantian dark magic at play here because if Person A had a good intention for someone else – but it made THEM feel good, we might not even have a truly good intention. There are some who argue that what makes something good isn’t its intended outcome but rather that it came the ‘good will’. I could say more here, but that’s a ‘looking glass’ for another day. What I will argue is that this approach fits the ‘thought that counts’ label – if the ‘thought’ or intention was altruistic then it must come with no discernible benefit for Person A.

Is it possible for a good intention and a good act to still lead to a bad outcome?

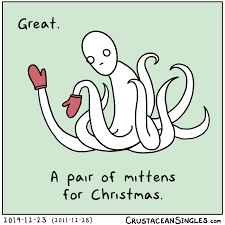

How about this. Let’s say that there is a relative in a family who has fallen on bad times, sadly not an uncommon scenario as we approach the end of 2020. Let’s imagine it’s Christmas and we have an extended family exchanging gifts. A wealthier relative (Person A) is beaming with excitement as she hands to the poorer relation (Person B) a large red envelope. The poorer relation opens the envelope with a gift card inside. The gift is a donation of $500 to a charity of their choice. Now, according to (1) we have good intentions (giving to charity) and arguably a good outcome (the benefiting charity). For me, this is still unforgivable. Why? Because it doesn’t benefit Person B. I would argue that the outcome is not just bad because the intention wasn’t to provide a good outcome for person B but that it negates any improvement to the poorer relations condition.

The reason why I like this scenario is that ‘giving to charity’ is good; giving gifts to those less fortunate is good – but when it comes to well meaning thoughts resulting in a poor outcome – to be forgiven, the forgiver has to be at the centre of the intention and the act.

With (2) we have to establish that, whilst performing Action ‘x’ – the person is truthful to (1). For example – as someone is physically performing the act that will be good for Person B – they are not harming anyone else or they are not changing their intentions. When establishing whether to accept conclusion (4) because of (3) we need to know that even when Person A was in the process of acting (2) – they were constantly mindful of the good they were doing for Person B. Also, let’s not forget Aquinas’s ‘Doctrine of Double Effect’ with Premise (2). The act may result in an unintended bad outcome but this would be ‘beside the intention’ – We are assuming for (2) that the final ‘product’ of that act presented to Person B be the result of good intention. For example I may choose to wrap a very thoughtful deeply perosnal Christmas present for my wife, but in so doing use up all the sellotape, cut a hole in the table cloth and present a box seemingly wrapped by a toddler. But you better believe I’ll tell her those things were all ‘beside the intention’.

For (3) we move from a Kantian ‘good will’ (doing good for the sake of its ‘goodness’) to a utilitarian perspective. We have to decide whether the total amount of ‘badness’ we experience as a result of (2) is firstly in proportion to Premise (1) but also as ‘bad’ as it seemed. Have I been so harmed – or has there been so much harm – that we couldn’t possibly forgive? Let me flesh this out a little more:

A bad outcome for Person B would most often be characterized by suffering, pain or the ending or stopping of something good (negation). For example, in my own experience this was a loss of ‘time’ on good things and increase in time on a laborious task. However, if I remember one of the problems with utilitarianism it is that we can never really know how and when the ‘utility’ ends. How many times in your life has something happened that you thought was terrible, but then ended up being the best thing ever? Here I am, feeling inspired by the bad thing that happened to me…does that now cancel out my initial feelings of frustration and return us to ‘neutral utility credit’ thereby filling my heart with forgiveness? Well, no – because I would still argue that in my case Premise (1) isn’t true! However, it does make for a good way of reflecting upon the result of some action on us. When we are harmed in some way by a good intention – properly reflecting on how harmed we really were may indeed lead us to a place of calmness and communication that we may not have thought possible. If we can accept Premise (1) and (2) but the awfulness of the outcome is difficult to bear – then we can’t accept conclusion (4) and the argument becomes inferentially difficult to prove. So, in reality we have to properly reflect on how ‘bad’ the outcome was for us.

It would appear that my argument can hold deductively – and I would propose that if each premise were true – then forgiveness is the correct response. Another way of viewing ‘good intentions and bad outcomes’ is to view it as a balancing act. If we can justify that intention was properly good and that the bad outcome was in proportion to the goodness and trueness of the intention or was at least not significantly harmful– we have grounds for forgiveness. In my own example – the act was unforgivable because ‘my’ Person A’s intentions were not wholly altruistic. There was clearly an intention to ameliorate their own level of labour by passing it on to me. There was nothing in the ‘act’ that demonstrated anything other than a desire to satisfactorily fulfil an obligation and I use the term ‘satisfactorily’ liberally. I would further argue that while performing the act, they were not mindful of ‘best outcomes’ either for me or for anyone else. This meant that I couldn’t logically accept (4) as a final outcome. I would however welcome any responses to my premised argument – and I would be fascinated to know if anyone could use it to reflect on their own examples.

Wherever you are in the world I hope the end of 2020 brings something brighter for 2021. Thank you for reading and engaging in my first year as a blogger. Your comments and readership means a tremendous amount to me.

dillon.

Leave a comment