Those of us in teaching have all experienced that exhausting final term at school. Behavioral problems from the usual suspects, every teacher running on empty but pushing ourselves and our charges over the line with as little drama as possible. We try to maintain discipline with increasingly wearied and fatigued cohorts of children (whose parents also hanker for the last day of school) as we continue to operate in the long shadow of Covid. But for certain there must be a discussion on how to address the behaviour problems encountered throughout the school over those final four months. In the concluding full staff meeting before planes are boarded, bars propped up or beds receive the dead weight of teacher ‘husks’ – the plan to address issues since January are disseminated and lo and behold out trots – ‘it’s time to go back to basics.

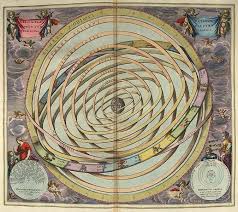

There’s a contrary itch in an idiom that states that to achieve progression we must first achieve regression – but I understand the mis en scene. As an appeal to the head – it’s about simplifying a complex operation and re-establishing how it works at its most basic level, and it’s easy to see how problems arise. How about this as an analogy: Over a period of time, an operating system that worked well with a basic structure whereby the main cogs ran simply and operated their primary functions without fault has incorporated into it more complex machinations. The belief being that the convoluted ways of working would either improve on the basic fulcrum of the system, meet new demands on the system or favorably tweak some issues. So far so good. Then, over more time these more convoluted moving parts start to take on the role as the new base system of operations and their more multifarious and intricate ways of working deemed ready to be front loaded yet further with systems thus causing more problems in of themselves instead of positively performing their primary function. The result is that folks look at the assembled muddle and say ‘Hey, remember when it worked really well because it was simple, and it did those simple things well…let’s just do that again!’

The biggest issue with my mechanical analogy is that whilst we could imagine a machine which at its most basic form worked seamlessly – the same cannot be said of a human constructed values-based organization. For when a school talks about going back to basics, for example requiring pupils to line up silently before they enter the classroom, you have to ask yourself: Are we doing this because lining up is a simpler more basic way of managing a classroom before learning? Or are we doing it because returning to some previous more basic way of working is just good in of itself?

My assumptions about ‘back to basics’ is twofold:

- It implies that more complex or convoluted ways of working are to blame for errors given the nature of complexity.

- That going ‘back to basics’ is of itself a virtuous action – but that this can be construed as a token phrase rather than really exploring values and individual well-being.

Let’s examine these two points:

I will take ‘lining up in silence outside the classroom before the lesson’ as an example of ‘back to basics best practice’. Let’s ignore that this strategy suits secondary school (where pupils move about from class to class) more than it would say an Elementary homeroom teacher. My problems are not situated there. Why is lining up in silence outside the classroom considered a fulcrum ‘basic’? Is it because it works simply, or is it because it feels good?

Let’s consider the issue that newer, or more convoluted ways of working are to blame (instead of keeping things simple) for a breakdown in school discipline before class begins. Maybe the newer system that was in place was that pupils could enter the classroom but had to get started on a task that had been set for them. In this instance, teachers would plan for an activity as students walked in that could be accessed independently that either would prepare for the main learning ahead or put them in a good cognitive mindset. This is sometimes referred to as ‘bell work’. Certainly, a more convoluted approach to the start of class discipline than lining up outside silently and awaiting the teacher’s permission to enter. However, the argument is that the new approach is more appropriate to promoting learning, though I don’t want to get bogged down by this. Let’s just state that ‘bell work’ is a more convoluted and load heavy approach than lining up outside silently.

Maybe there had been a problem with the ‘bell work’ approach because a teacher had gone from say a GCSE history class with 16-year old’s straight to a Year 7 class with eleven years old’s and they didn’t have time to prepare a suitably engaging activity for them to dive in to. Possibly, the previous period of teaching had been fraught, and the teacher needed a five-minute breather and lining the pupils outside gives them the space to reset? Both perfectly rational reasons to have children line up outside.

However, that the more convoluted, but arguably more learning focused start to the class could at times be difficult to achieve, does not necessarily mean that it in itself is at fault for a breakdown in class discipline. Its more complex nature compared to simply lining them up does not necessarily make it at fault. Maybe the convoluted ‘bell work’ approach works, but meaningful help needs to be offered on supporting that teacher with different strategies when switching between grades. In this operating system (discipline and order before class) ‘bell work’ is a great way to engage children in being ready to learn – there’s nothing wrong with it. Therefore, to that end, there’s no need for a return to basics – we just need to take more time and give more care to embed a newer way of working because it’s not 1955 anymore and research has moved us on. Oops! Did you see what I did there? I threw in a little ‘values’ wink. Am I suggesting that when we talk about going ‘back to basics’ we are talking about a more ‘simpler time’ rather than a simpler way of working? There are ways of working throughout history that still work today…but sometimes ‘back to basics’ isn’t an appeal to review the machinations of a way of operating to ensure the foundations are sound – for at its worst, it’s a values laden treat: churned creamily with simplicity, dipped in sumptuous good old fashioned values and sprinkled with straight talking – no nonsense sparkles. Mmmmmm…so comforting.

As it happens there is, I think, an argument that going back to basics is in of itself a virtuous action. I make a play on how it can be used to give a false sweet sense of comfort that things will improve irrespective of the context, but for me that is where the issue is. If you were to say to a group of beleaguered or confused people that the plan was to go back to basics – there may well be a sense of relief and a hope for a more direct path. That said, it’s virtue is not located in its promise for a simpler time (that may have never really existed, except for false memories or dominant discourses) – it is its link to asceticism. That is its virtue.

Asceticism, in its strict religious meaning, is stark self-discipline. A rejection of any indulgences; abstention from practices that may cause erring or swerving the most pious path. If I can dilute this harsh definition – I think it would be fair to say that most religions hold it to be true that living a simpler life, a life less over burdened by technology or one that shrugs off over complicated or convoluted ways of thinking or acting , as a ‘good’ life. And intuitively we feel it to be so – think of detoxifying, de-cluttering, breaks from social media…these are viewed as important if not necessary ways of recentering and recalibrating what is important and what works. So much like our machine analogy at the top – seen through the lens of a virtuous action; going back to basics from a personal almost ‘spiritual’ way will inevitably offer some insight into why a way of being or acting is causing consternation or a lack of productivity. And there is benefit in that. There is benefit in going to back to basics both in personal reflection and in reviewing an operating system that may be at fault.

So what’s the problem?

Therefore, the problem arises when going ‘back to basics’ is a token gesture. This idiom should not be free from constructive criticism. When someone tells you they are taking something ‘back to basics’ are they offering a plan to reflect and review on a way a thing functions? A chance to re-establish what we know works and really try and embed newer systems to work well and not reject them because complex necessarily equals complications. Are they offering the space and time for an individual to re-calibrate and re-assess what is ‘good’ for them? Giving folks time to mentally recharge. Or are they simply hoping you’ll hear in your mind the faint lilting chimes of the ice cream truck – wistfully recalling how you once could leave your doors unlocked at night, no one had a mobile phone that now ruins everything and a tenner could buy you a movie ticket, fish and chips on the way home and still have change for a mortgage. And in your reverie, you agree to whatever is suggested because ‘back to basics’ feels like it can only be a good thing, right? Don’t be afraid to challenge this idiom when it’s presented to you whether it be an appeal to the heart or the head – but always accept a scoop of ice cream.