The problem with holidays is one has time to scheme. The day-to-day pressures of working and upholding a work persona mean that when one’s time is one’s own and the inbox is ignored and the work persona shelved: new, interesting, ambitious and creative projects come to the fore. Currently, the ambitious and creative project hamster which spins the wheel in the back of my head and occasionally and loudly nibbles on toilet roll is what I would do for a PhD. More often than not, the rustlings and nibbling’s of project hamster are drowned out by the bellows of students and vicissitudes of everyday life. Like I say, that’s the problem with holidays.

Men are a problem. I would confidently claim that in a substantial amount of a child protection social worker’s case load the bulk of the load is caused by a man: a man who is absent causes problems; a man who is present causes problems. They’re just problematical. Problematic men in a child’s life within a child protection context would be fairly obvious – risk of abuse. However, their absence from a child’s life can place significant strain on the normative parenting workload of a single parent. Furthermore, the lack of a good role model can also be detrimental to a child’s sense of identity and esteem. However, not all male parenting figure’s absences are linked to child protection. Oftentimes, the nature of a significant male role model’s absence in a child’s life is simply due to expectations and pressures of work, and within the context of international schools – the earning divide. This is especially felt in countries where the wife (though not exclusively) or ‘accompanying spouse’ can’t get a work visa which places the ‘breadwinner’ burden firmly on the male side. The reality for a lot of hard-working and loving fathers is that their ‘problematic’ absence is not due to maleficence, but simply work commitment. Another significant variable, especially for expat families, is the lack of a family support network. All put simply, in my experience in international schools, dads are away a lot. I know this because the children tell me. And they tell me that whilst they understand why their dads are away…they miss them.

Parenting can be problematic. And in child protection social work it can become unsafe and concerning. When child protection social workers are faced with overwhelming evidence that a child is at risk of significant harm, they can use legal powers or ‘Care Orders’ to remove that child from the home (often temporarily, sometimes permanently). During that period of separation and before any final court orders around adoption happen, the biological parents retain their legal status of ‘parent’ and all the responsibilities therein, however the local authority is given a new epithet: Corporate Parent. Now, I like the phrase ‘corporate parent’. That said, I understand the grind between something as innately caring and purposeful as ‘parent’ and something as myopic, calculative and materialistic as ‘corporate’. However, parenting can be a hot boiling mix of values, ethics and psychology that could benefit from the cubed iced drops of policy, procedure and measurable outcomes. What I liked most about the phrase ‘corporate parent’ during my time as a social worker is it separated me from the role. When I was working with a child, I could exhibit the unconditional regard for safety and the intuitive show of compassion and care linked inextricably with good parenting but had that corporate parent embossed tempered glass panel between us that allowed me to make rationale and evidenced based decisions for what was best – unfettered by any ‘loving obligation’.

Well, that was theory. In practice it was incredibly hard – especially when the ‘Body Corporate Parent’ (senior leadership) insisted on decisions that either made no sense or clearly didn’t know the child. However, I digress.

Can I say, the hamster in my head is feeling the love right now? I am metaphorically cleaning out the cage, refilling the water and putting a few treats in the bowl here. To be honest, it was beginning to smell a little bit.

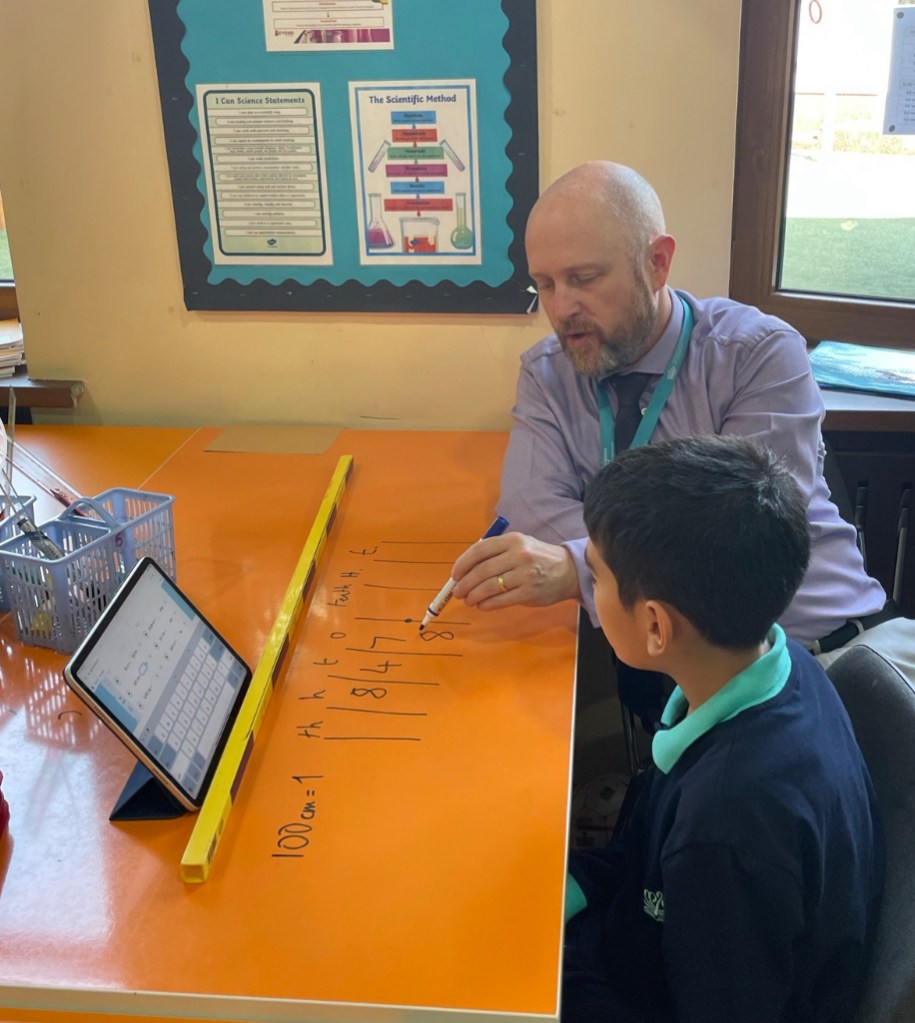

The PhD idea? I am essentially talking about non-dangerous absent fathers and the role of the corporate parent – in this case ‘teacher’ and more specifically: ‘male primary school teacher’. Where am I going with this within an international school context and what does this have to do with a PhD? It would be my view that male primary school teachers have a corporate parenting role to play in their student’s lives within certain specific contexts. I would almost go as far as an ‘obligation’ to do so (if I was feeling more controversial) And whilst there are professional, ethical, and sociological issues with this claim (and that I would be made to refute) ultimately, teachers do share the parenting load; they do have a legal duty of care anyways and, because of the problem of men – male teachers should be prepared to pick up the extra heavy lifting in certain contexts as a corporate parent.

Cage is clean, hamster is happy. I’ve made a lot of claims here about fathers and family demographics in an international school setting – but I reckon with a good academic library, and some of my own qualitative research, I could substantively prove this to be the case. I’ll be arguing some pretty interesting points from education philosophy, sociology and ethics but again, I would probably enjoy that! But, what do you think? I would welcome the views of any readers of this piece on the statement:

Male Primary School teachers have a corporate parenting role to play within the lives of children with absent fathers.